Want more expert insights on the topic of pay equity? Access our entire Pay Equity Deep Dive Series.

As discussed in our first pay equity deep dive, we break down the process of conducting a pay equity review into five phases:

- Setting the Foundation

- Model Development

- Preliminary Results

- Fair Pay Strategy

- Ongoing Monitoring

Once you’ve created your Pay Analysis Groups (PAGs), consolidated and refined your Wage Influencing Factors (WIFs), and conducted reliability and robustness testing, you’re ready to develop your fair pay strategy.

Your fair pay strategy involves:

- Deciding where to remediate

- Selecting a remediation strategy

- Conducting an employee-level review

Where to Remediate

In deciding where to remediate, you’ll likely flag PAGs in which there are statistically significant pay disparities based on gender, race/ethnicity, or other protected characteristics. The statistical significance of a pay disparity is typically measured using a 5% significance level (i.e., p-value ≤ 0.05). This is a commonly used significance threshold and indicates that there is a 5% chance or less that the result is due to chance.

While statistical significance is the gold standard in pay equity reviews, you may want to consider practical significance as well. Practical significance indicates whether a pay disparity is meaningful from a business perspective and warrants attention, regardless of statistical significance. A consideration of practical significance commonly comes into play in the following circumstances:

- Very large group with a small pay disparity: Very small pay disparity (e.g., <0.5%) can be statistically significant when examining a large group (e.g., entire organization or division).

- Very small group with a large pay disparity: Very large pay disparity (e.g., 5%) may not be statistically significant when examining a small group (e.g., job, department).

In the first case, you may decide not to remediate a statistically significant pay disparity that is smaller than a specific threshold. In the second case, you may decide to remediate a non-significant pay disparity if it is larger than a specific threshold.

For example, under the EU Pay Transparency Directive, pay disparities exceeding 5% will trigger a joint pay assessment. Therefore, when analyzing employees in the EU, we recommend addressing disparities above 5%, regardless of statistical significance.

Moreover, it’s conceivable for a company to have no statistically significant disparities in any of its PAGs yet have a statistically significant or practically significant company-wide disparity. To reduce a company-wide disparity, it may be necessary to address PAG-level disparities above a certain threshold (e.g., 2-3%), regardless of statistical significance.

A Few Useful Concepts

Before delving into a discussion of remediation strategies, below are some useful concepts we’ll be referring to.

Class Effect: The class effect refers to a pay disparity as revealed by a regression analysis. For example, if a regression analysis reveals that — after accounting for legitimate, compensable WIFs — Black women are paid 4% less than White men, this is a class effect. When reporting this figure, it’s often converted to a cents-on-the-dollar figure. In this example, we would say that Black women are paid 96¢ for each $1 White men are paid.

Impacted Class: Demographic class with a pay disparity. In the example above, Black women would be members of an impacted class.

Neutral Pay Prediction/Predicted Pay: Using the results of a regression analysis, we can compute an employee’s predicted pay based on the legitimate, compensable WIFs included in the model. By design, this prediction is neutral to an individual’s demographic characteristics. A class effect shifts all members of a class away from their neutral prediction. In the example above, Black women are below their neutral prediction by 4%.

Individual Effect: Besides the neutral prediction and the class effect, the remaining portion of an individual’s actual pay is the individual effect. It captures the portion of an individual’s pay that is due neither to the neutral prediction nor to the individual’s demographic characteristics (i.e., class effect). This individual effect can be positive, in which case it partially or wholly offsets the class effect. Similarly, this individual effect can be negative, in which case the individual’s actual pay is even further below the neutral prediction than the class effect implies. In either case, the combination of the class effect and the individual effect measures how far an individual’s actual pay is from their neutral pay prediction.

Standard Deviation: Standard Deviation is a general term that refers to dispersion of data relative to its mean. In our context, standard deviation is a way to measure how far an individual’s actual pay is from their predicted pay using standardized units. We use it in place of dollar or percentage differences. Using standard deviation units facilitates comparisons across individuals. For example, we may want to look at individuals whose actual pay is more than 2 standard deviations below their predicted pay.

Selecting a Remediation Strategy

There are a variety of ways to remediate a pay disparity within a PAG. Here we outline three potential strategies.

1. Class Effect Strategy

Under this strategy, all members of an impacted class (i.e., a demographic class with a pay disparity) are eligible for a uniform percentage pay adjustment to address the class effect revealed by the regression analysis. For example, if your regression analysis reveals that Black women in a PAG are paid 4% less than White men, all Black women in the PAG — regardless of their actual pay level — receive a 4% pay increase.

This strategy is straightforward to implement since members of an impacted class are eligible for the same percentage pay adjustment. It also is the strategy that most directly addresses the pay disparity identified by the pay equity analysis.

The primary objection associated with this strategy is that members of an impacted class whose actual pay exceeds their predicted pay (because their individual effects are large and positive) are eligible for an adjustment.

2. Class + Individual Effect “Broad” Strategy

In a PAG with a class disparity, every employee whose actual pay is less than their predicted pay is eligible for a pay adjustment. Furthermore, the amount of the adjustment depends on how far away the individual’s actual pay is from their predicted pay. That is, larger adjustments will go to those who are further away from their predicted pay. Because this approach targets the net difference between actual pay and predicted pay, and that net difference is the sum of class and individual effects, we refer to this strategy as “Class + Individual.”

This strategy results in a fair process in which all employees paid less than predicted, regardless of their demographic class, are eligible for an adjustment. However, this approach is less effective at addressing a class-based pay disparity because:

- Some individuals who are not part of an impacted class will have their pay adjusted.

- Members of impacted classes with large, positive individual effects will not be adjusted.

Moreover, this approach is costly to implement because some members of non-impacted classes receive an adjustment, and resources are spent removing some individual effects (versus focusing on class effects only).

3. Class + Individual Effect “Focused” Strategy

This strategy is like the Class + Individual Effect Broad strategy, with the exception that only members of an impacted class are eligible for a pay adjustment. That is, only members of an impacted class who are paid less than predicted are eligible for an adjustment. This strategy is more efficient than the broad method since it limits eligibility for pay adjustments to those who are part of an impacted class.

Illustrative Example of Remediation Strategies

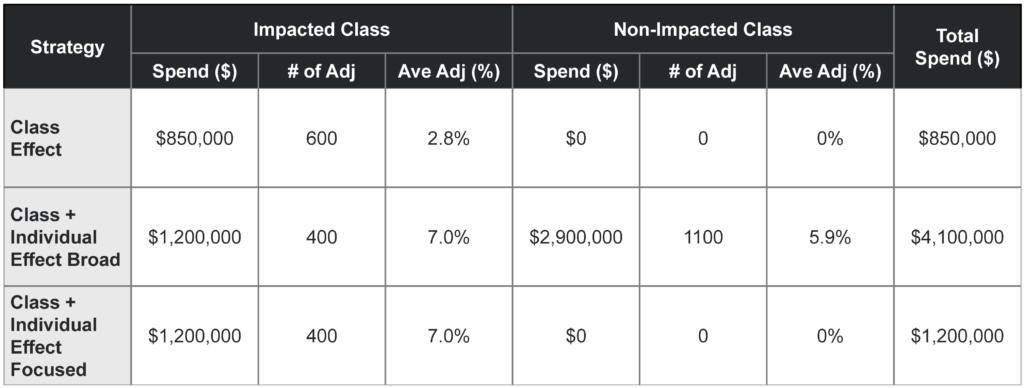

The table below shows an illustrative example of the three remediation strategy options. Under the Class Effect strategy, remediation costs for members of impacted classes are $850,000. This results in 600 pay adjustments with an average adjustment of 2.8% of annual salary. Under this strategy, individuals who are not members of an impacted class are not eligible for remediation.

Under the Class + Individual Effect Broad strategy, fewer members of an impacted class receive an adjustment. This is because only those whose actual pay falls below their predicted pay are eligible for an adjustment. In this case, 400 of the 600 members of impacted classes are paid less than their prediction.

These 400 individuals receive an average adjustment of 7%, resulting in a remediation cost of $1.2 million. As part of this strategy, members of non-impacted classes are also eligible for an adjustment if their actual pay falls below their predicted pay. This results in an additional 1,100 individual adjustments, with a cost of $2.9 million. Under this strategy, the total remediation cost is $4.1 million.

Under the Class + Individual Effect Focused strategy, the cost of remediation for those in impacted classes is the same as in the Class + Individual Effect Broad strategy (i.e., $1.2 million for 400 adjustments). In this case, members of non-impacted classes are not eligible for remediation. Like the Class Effect strategy, this Focused strategy just considers impacted classes. It is more expensive than the Class Effect strategy because it is spending resources to remove individual effects as well as class effects.

In our experience, the most common strategy selected is the Class + Individual Effect Focused strategy. This strategy allows an organization to address pay inequities, while focusing adjustments on members of impacted classes who are paid less than their neutral pay predictions. The Class + Individual Effect Broad strategy is seldomly selected. The Class Effect strategy is recommended when you have concerns that WIFs included in your pay models may not be generating accurate predicted pay estimates.

This may occur when WIFs you believe to be highly relevant are not included in a model due to lack of structured data. Such omitted WIFs may impact the predicted pay estimates that the Class + Individual Effect Focused strategy seeks to eliminate.

* * * * * *

Stay tuned for Part V of our “Pay Equity Deep-Dive” series, which will continue our examination of remediation strategies and cover budget and allocation considerations.